Energies | Cultured

Oct 23 2024

By John Vincler

Our Critic Resorted to Trespassing to See This Artist’s Work. Here’s How You Can See It—and the Exhibition It’s a Part Of—(Legally)

John Vincler praises “Energies,” a new exhibition at the Swiss Institute, as one of the “boldest curatorial feats” in his recent memory.

Don’t do what I did. I slipped into the East Village courtyard at 519 East 11th Street, having caught the gate before it latched, after a postal worker exited. I wanted a closer look at a mural within by the Antwerp-based Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga, as it’s barely visible from the street. The wall-spanning painting centers upon a woman tangled in gnarled wires, as another woman stands nearby, unencumbered, except for the child she accompanies. The diagrammatic composition, which unfurls across the wall like a scroll, charts interconnections between factories, agriculture, and urban living. Turning to exit, I found myself trapped in the courtyard, without a latch or handle on the yard side of the gate. So, I climbed a ledge to hop the wrought iron and brick fence, and then dodged the suspicious looks as I landed back on East 11th.

Nkanga’s mural is an offsite element of the exhibition “Energies” at the Swiss Institute, just a few blocks away—11th Street was my first stop because the co-op building there, and its legacy, are central to the show. But can—or should—we think about the history of an apartment building in an art exhibition?

519 East 11th Street is one of New York’s first sweat equity co-ops, where renters in the 1970s became owners. In lieu of mortgage payments, residents undertook maintenance and construction projects to establish their cooperative ownership. But these residents took their collective action further with the radical idea of installing a two-kilowatt wind turbine on the roof, as well as an array of solar panels, which allowed for the building to stay illuminated during the citywide blackout of 1977.

That same year, the resourceful co-owners won a case against Con Edison, disrupting the power company’s near-monopoly by forcing it to give the building credit for the excess power they fed back into the grid. The case established the legal groundwork for the widespread use of solar in residential buildings in New York today. (In fact, following the Climate Mobilization Act of 2019, new construction in New York now must feature roofs partially covered with either a green roof or solar photovoltaic electricity generating systems.)

“Energies” sprawls across the three floors and rooftop of the Swiss Institute, and into the neighborhood beyond, in one of the boldest curatorial feats I’ve witnessed at an art institution in recent memory. The show is curated by the Swiss Institute’s entire curatorial team, including Director, Stefanie Hessler; Chief Curator, Alison Coplan, with KJ Abudu and Clara Prat-Gay. What makes this exhibition so good—so remarkable in the current art landscape—is that it succeeds not solely on the merits of its eclectic range of art from an international roster of nearly 20 artists and collectives, but because it creates a vivid scenario for thinking about pressing issues of contemporary life: ecological catastrophe, housing scarcity and precarity, and economic inequality. And it offers models for redress in the form of community organizing, DIY engineering, and even legal challenge.

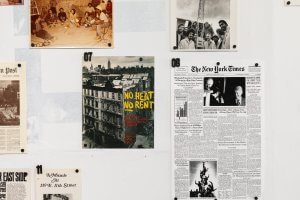

Visitors to “Energies” are met first by a wall, constructed by New Affiliates—an architecture and design studio led by Ivi Diamantopoulou and Jaffer Kolb—from the discarded remnants of dismantled exhibitions sourced from throughout the city. Titled Drywall is Forever II, 2024, it materializes the tremendous amount of waste created by this churn for exhibiting the ever new.

The freestanding structure is also used to display an array of archival documentation about the co-op building and its community, from photographs and legal records to the original blade from the 11th Street rooftop wind turbine, which crowns this agglomeration of information. Also amid the salon-style layout is a 1982 painting by artist-resident Ruth Nazario that depicts a neighborhood block party, seen, hauntingly, from between the Twin Towers. On neighboring walls, Becky Howland’s environmentally-themed multimedia works hang near a poster, from the same year, for ABC No Rio, the anarchist art space she helped to found in a squat on the Lower East Side. (The venue survives today as a nonprofit with a new building now under construction at the address of their original space.)

Other works in the room telescope outward to broader contexts, such as Joar Nango’s towering, light-filtering sculpture Skievvar #2, 2024, which is composed of dried halibut stomachs (a traditional window material used by Indigenous, Sámi communities), and Ximena Garrido-Lecca’s Yacimientos, 2013, a two-channel video shot in the Peruvian town of Cerro de Pasco, which highlights the environmental cost of mining there—a practice that, at a glance, can resemble land art. The film captures the terrible beauty of extraction. Around the corner, Vibeke Mascini’s conceptually gnomic installation, Instar, 2024, consists of a forklift dolly carrying a pallet of large batteries storing energy derived

from the incineration of confiscated cocaine—a nod to resources consumed in the war on drugs.

On the second floor, a selection of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Energy Tree drawings, 1970–75, are on view, alongside an original copy of his 1976 application to the Guggenheim Foundation for “A Resource Center and Environmental Youth Program for Loisaida.” Notably, Matta-Clark uses the Spanglish term for the Lower East Side, which would be adopted for the name of an arts-focused and Puerto Rican-led community development organization, founded two years later (the year he died). And, in another offsite intervention, a short distance away, at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, the artist’s Rosebush, 1972/2024 can be found. The piece, a cage like those for supporting climbing plants—made of a material to echo the church’s wrought iron fencing—has been refreshed with a new rosebush and a plaque, reactivating the work after years of neglect and anonymity.

The neighborhood’s ties to Puerto Rico are underscored by Gabriella Torres-Ferrer’s video installation, which displays live feeds from four sites on the island, each chosen to highlight an area where infrastructure was impacted by Hurricane Maria in 2017. On the wall behind, Gina Folly’s starkly ambivalent photographs report from another distant place. The images depict a solar-powered, floating milk production facility—yes, cows on a barge—in the port of Rotterdam.

Cumulatively, the far-flung works bring history into the present, and—refreshingly—the exhibition reminds us of what is possible. Here, on display, are not just the speculative dreams and play-acting of artists. The show’s curators reveal and document transformative action that brought to life a community, created a shared home, and undertook the real work of securing power. In sketching this local history, and in gathering together contemporary work around it, “Energies” asks what might it look like if a similar task was undertaken today.