Against the Romance of Community | City Lab at The Atlantic

Oct 14 2016

In 1973, the village of Rosendale, New York, was in the throes of a civic identity crisis. The small incorporated community, situated within the limits of the larger Rosendale township, was practically broke, due to the long decline of the cement mining industry that had bolstered it for centuries. Out-of-work families moved away, and overtaxed businesses fled from the village’s main street to the township’s business route. Young hippies and artists from New York City flocked to cheap, run-down properties, clashing with conservative old-timers. Village and town leaders sparred over how to handle noise complaints and snow-plow rights, as water and sewer bills skyrocketed for the village’s dwindling residents. Rosendale’s center could not hold.

Raivo Puusemp saw an opportunity to intervene. A conceptual artist working at nearby SUNY Ulster, Puusemp was fascinated by the social dynamics of suggestion. In one recent work, for example, he’d told a fellow artist about how he wished he had time to cordon off a section of sidewalk to see how people would move around it. Puusemp said he hadn’t made time to do it. The friend proceeded to rope off the path himself, and pedestrians reacted in all kinds of ways. Puusemp had pulled off a domino-ing act of persuasion. “He was interested in ways of placing his work in the world without ever making it,” says Laura McLean-Ferris, an adjunct curator at the Swiss Institute, a contemporary art space in New York City, where an exhibit on view through October 23 features Puusemp’s work.

Clearly Puusemp was far from a politician, and he’d only just arrived in Rosendale—he’d learned about the town by its proximity to his favorite rock-climbing spots. But what might happen, he thought, if he ran for mayor? Perhaps he could use a process of suggestive communication to guide Rosendale to a place of financial and bureaucratic viability. Though he would never verbally characterize his political actions as art to Rosendale citizens, he would treat them as such, taking the village as his materials, the municipal boundaries as a spatial frame, and a mayoral term as his time limit.

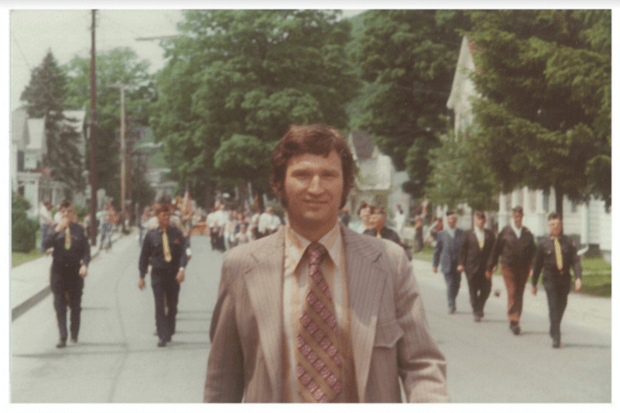

Puusemp confided the plan to some artist friends, many of whom were alarmed by the prospect of manipulating unwitting citizens. But Puusemp insisted that he had no specific intention, other than to do good. In 1974, he campaigned for office, promising to reorganize the village police force and restore its sewer and water systems. His positive platform lent him credibility among voters, and he swept the election. “It was the first opportunity people had in a long time to see change as possible,” Puusemp, who now lives in Utah, tells CityLab. “Things had just seemed intractable.”

Once in office, it became clear to him that the only path forward was to dissolve the village of Rosendale into the township, pooling resources to fund essential services, rather than village residents having to essentially pay double. But residents had strong emotional attachments to their village identity. So Puusemp did everything he could to convince them of the fact that, as he puts it now, “cities are voluntary organizations that don’t have to exist.”

He commissioned economic reports, held public meetings, and presented the case to citizens and politicians, arguing that disincorporation would benefit township and village alike. The suggestive power of radical transparency worked—and did so incredibly quickly. “It was not a question of deluding or lying or falsifying anything,” he says. “It was simple mathematics.”

Less than six months after his election, a public referendum held on dissolution was passed in a landslide—the village would be abolished, and municipal services would be shared. A few months later, Puusemp resigned as mayor, vowing never to run for office again. That abdication crucial evidence of the difference between his work as an artist and the the work of any regular elected official, he says. “I think it’s about the intent,” he says. “People looking for power or influence would have just capitalized on that success and gone on to do bigger things. But for me, this was an opportunity to do a self-contained political piece.”

At the urging of his close friend, the artist Paul McCarthy, Puusemp gathered newspaper clippings, letters, and public notices that chronicled the Rosendale project, publishing them as a single volume titled Beyond Art – Dissolution of Rosendale, N.Y. Now, in an exhibit titled “Against the Romance of Community,” the Swiss Institute explores those documents alongside other artworks focused on how communities behave, interact, and identity themselves.

Puusemp’s Rosendale project, and another work from the 1970s—a conceptual video by Lawrence and Anna Halprin documenting a community leadership training in San Francisco—bookend more contemporary works that draw on urban planning, architecture, and mass media to explore notions of group identity.

It’s an important time to think about these concepts, says McLean-Ferris, in a landscape saturated by nationalistic fervor. The rise of Donald Trump in the U.S., the outcome of Brexit in the U.K., and a surge of global anti-immigrant rhetoric pose urgent questions about how and why citizenships cluster together. “We were thinking about the current political situation, and the ways in which people are being persuaded and guided to form and identify themselves as communities,” she says. In Rosendale, people were able to break from their nostalgic ideas of how the town had been previously, in order to evolve it. It just so happened that an artist helped them do it.

Decades later, Puusemp says he doubts many citizens ever realized that his time as a very popular mayor was actually a work of art. He suspects he’s not too well remembered in present-day Rosendale, which is enjoying a second renaissance as a destination for priced-out Brooklyn creatives. As an artist, Puusemp isn’t entirely active anymore. But he’s glad to see a surge of interest in his Rosendale project, which was also recently featured at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art and Dublin’s Projects Art Centre. Being a mayor for art’s sake “was a weird thing to be doing,” he says. “But it worked out best for everyone.”