FADE IN 2: EXT. MODERNIST HOME – NIGHT | Frieze.com

Jul 31 2017

By Eli Diner

As sites go, you could do a lot worse than the (somewhat chaotically-named) Gallery-Legacy of Milica Zorić and Rodoljub Čolaković to launch a new Balkan art initiative. The building, located in Belgrade’s plutocratic enclave of Dedinje, is a large modernist house – all glass and right angles – spruced with a few contemporizing additives. It isn’t, however, the façade or the valences of style so much as the past lives of the building that make it appear like a totem of reinvention and historical vagary. If these walls could talk!

Built in 1934, the house originally belonged to a Jewish family, but following the German occupation and the establishment of the collaborationist Government of National Salvation in 1941, it was seized from its owners. It was, in turn, purchased by Milos Stratimirović, only to be confiscated after the war when he was imprisoned as a collaborator. The next residents were the eponymous Čolaković and Zorić. Both were revolutionaries before the war; he, the former, helped translate Marx’s Capital (1867) into Serbo-Croatian and served as an important political figure in postwar Yugoslavia, while she, the latter, became a textile artist. They donated the property – and their art collection – to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade (MoCAB), which began using it as an exhibition space in 1980. Facing financial difficulties following the transition to capitalism, MoCAB ended up renting out the villa to a gangster, Darko Ašanin. And it was in the courtyard of the house, watching the 1998 World Cup, where Ašanin was gunned down.

On 14 July, that very courtyard was crawling with beefcakes, in jeans and white t-shirts. They removed their t-shirts, climbed into the fountain and painted each other’s backs – a performance orchestrated by Danai Anesiadou, in homage, apparently, to Denys de La Patellière’s 1968 comedy Le tatoué (The Tattoo). With the house now an art space once more (overseen again by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade), the performance formed part of the opening of the exhibition ‘FADE IN 2: EXT. MODERNIST HOME – NIGHT’. A series of identical posters by Raša Todosijević made in 1997, advertising an unmade film called Murder, looked down on the scene from the windows of the house, intended, it would seem, as an evocation of Ašanin’s bloody demise.

‘FADE IN 2 …’ is the first exhibition supported by Balkan Projects, an organization founded by Serbian movie star and art collector Marija Karan – both the actress and organization are based in Los Angeles. The aim of Balkan Projects is to foster exchange between artists and institutions in the former Yugoslavia and that immense, interknit international art world whose boundaries are harder to delimit.

Organized by Simon Castets, director of the Swiss Institute in New York, and independent curator Julie Boukobza, ‘FADE IN 2 …’ centres around art about movies or, at its more focused moments, art about the way art figures in movies. Carissa Rodriguez’s La Collectionneuse (The Collector, 2016), for example, consists of several recreations of the razorblade sculpture that appears in Eric Rhomer’s 1967 film of the same name. The appearance of Albert Bierstadt’s landscape Mountain Scene (1880-90) in both The Age of Innocence (1993) and The Hunger Games (2012) serves as the basis for Mathis Gasser’s Grasshopper (Mountain Scene) (2015-16), in which he reproduces the original painting twice and hangs the pair beside a screen playing footage from the 2015-16 TV adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Man in the High Castle, a series that deals with the role of cultural artefacts in imagining counterfactual histories.

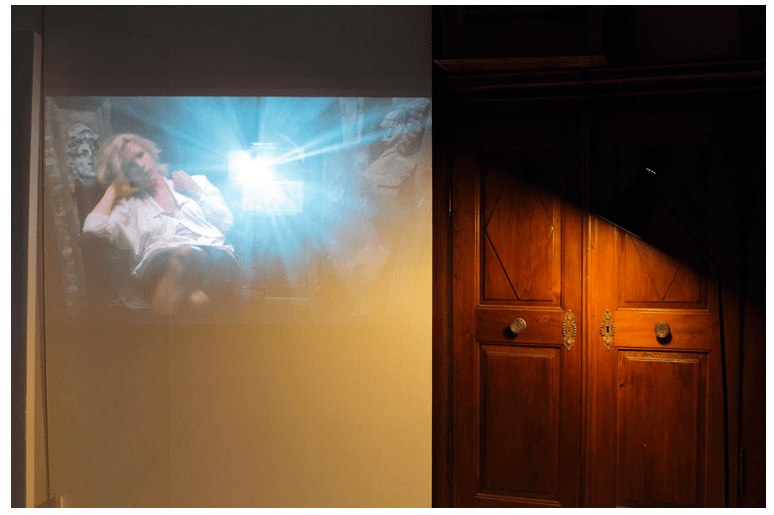

The exhibition is a sequel to ‘FADE IN: INT. ART GALLERY – DAY’, mounted at the Swiss Institute last year, and it features some of the artists that you might expect, given the theme: Alex Israel, represented by a recreation of the ovoid crystal tchotchke at the heart of the 1983 film Risky Business; Christian Marclay, whose video Made to be Destroyed (2016) presents a montage of scenes culled from Hollywood movies that involve art being demolished. But there are some more interesting inclusions as well: Benjamin and Stefan Ramírez Pérez’s Confluence (2017), a documentary portrait of the Serbian pop singer Dorris, is fascinating, and Brice Dellsperger, always brilliant, shows the latest in his ‘Body Double’ series (1995-ongoing), which sees scenes from movies reimagined in high-camp, psychedelic drag.

In keeping with the Balkan Projects mission, the show also includes a significant number of artists who might be identified with the Balkans. Todosijević, for example, is an elder statesman of Serbian art and was a key figure in Belgrade’s radical performance art scene in the 1970s. Most of the others, however, like Darja Bajagić, Dora Budor, Aleksandra Domanović, and Bojan Šarčević, live and work in Western Europe or the United States, some of them having left Yugoslavia as young children. What, then, does it really mean to create dialogue between Balkan artists and those from elsewhere when so many of the former have already become the latter? We’ll have to see what Balkan Projects has lined up next; I’m told a second exhibition is in the works for 2018, but as yet nothing has been announced. Perhaps it will focus on this diasporic dynamic.