Harald Szeemann | Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us | The New Yorker

Jul 15 2019

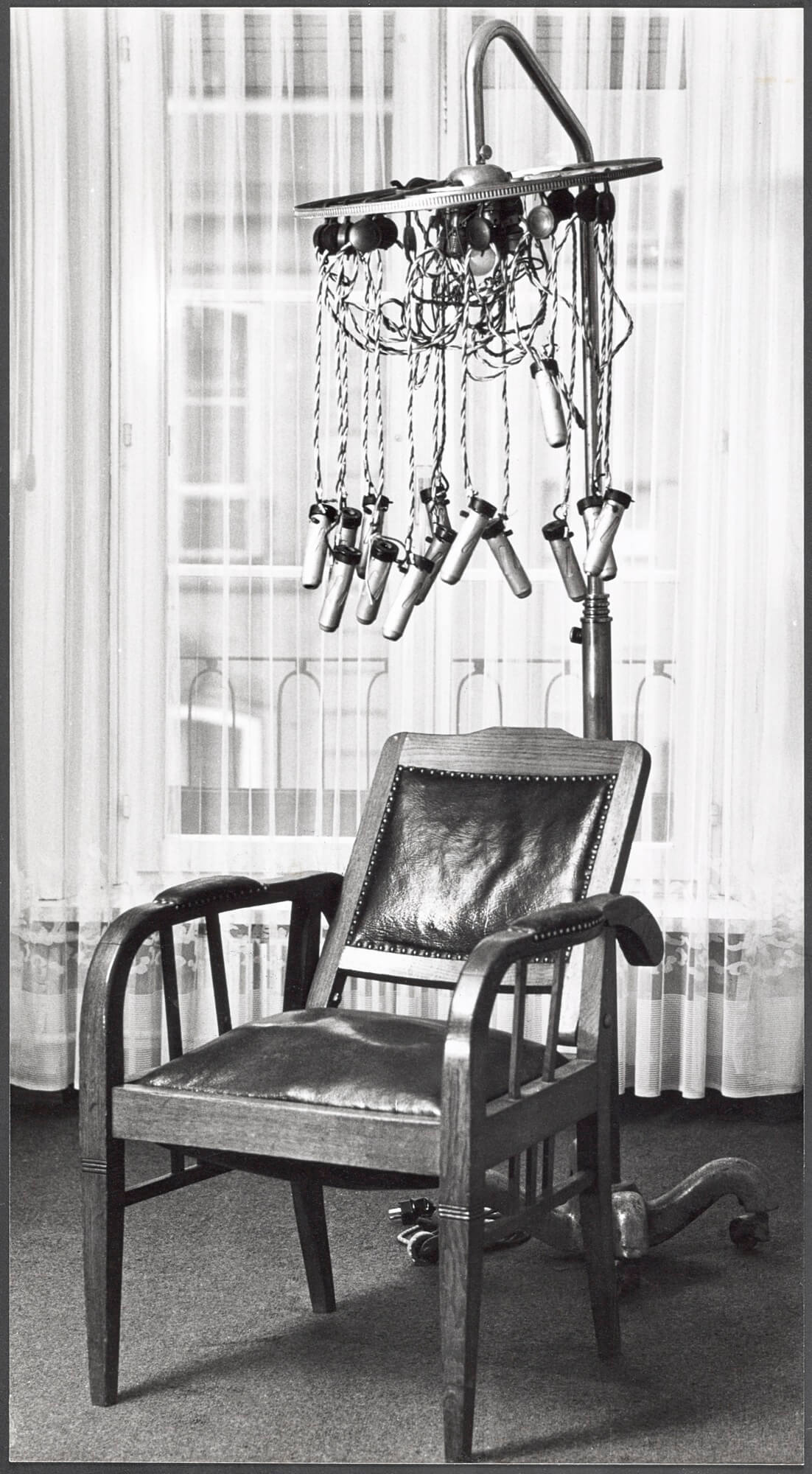

The most bizarre exhibition in town this summer bears on the prevalence, lately, of “curating” as an honorific for the organizing of practically anything by just about anyone. “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us,” at the Swiss Institute, re-creates a show that the revolutionary, for good and ill, Swiss curator-as-auteur Harald Szeemann (1933-2005) mounted at his home, in Bern, in 1974. About twelve hundred objects, cunningly arrayed, document the life and work of Szeemann’s paternal grandfather, Étienne, who was a hairdresser with a peripatetic career in Europe. Most of the items—furniture, family photographs, a lethal-looking early permanent-wave apparatus, advertisements, religious kitsch, wigs, tools, mannequin heads, letters, no end of tchotchkes—belong to the Getty Research Institute, in Los Angeles, where a Szeemann archive and his personal library occupy more than half a mile of shelf space. Glenn Phillips, the head of the Institute’s modern and contemporary collections, describes “Grandfather” as “a project that for many curators has served as both a fantasy and a symbol of curating in its purest form—exhibition making as a creative act.” Madly grand and deadpan daft, the show essentializes a strange glamour that seems to have leaked from the art world into the culture at large.

Curators used to be mainly caretakers of art works and facilitators of their exhibition. Szeemann blew past those roles with a hugely—infinitely, almost—influential show, exactly fifty years ago, at the Kunsthalle Bern, of which he had become the director in 1961, at the age of twenty-eight. (Kunsthalles are non-collecting museums.) “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form” gathered recent works or hosted the creation of new ones on the spot, by sculptural and conceptual artists—from the German magus Joseph Beuys to the boundlessly innovative American Bruce Nauman—to illustrate Szeemann’s brainstorm of art as a class less of things than of behaviors. His timing was sensational. Throughout the nineteen-sixties, contemporary art, chiefly Pop painting, had soared in popularity and been rapidly commercialized. Szeemann’s thesis consolidated a generational revolt, among intellectually inclined and politically alienated art-school graduates, against conventions of artistic form and taints of marketing. He initiated a schism, which lasts to this day, between the sphere of the art world which is dominated by dealers and collectors and the one that is administered by institutions of contemporary art. Private money fuels the first, public and philanthropic money the second.

At “Attitudes,” nothing forbade you from buying the American Robert Barry’s “Uranyl Nitrate” (1969), now re-created inconspicuously (you have to be told of it) atop a structure on the roof of the Swiss Institute, as an addendum to “Grandfather.” But imagine being responsible for four one-gram vials of a radioactive uranium salt with a reported half-life of four and a half billion years. Other artists physically assaulted the Kunsthalle, cutting into walls and ripping up a plaza. The American Walter De Maria installed a telephone that he called into now and then to converse with whoever answered it. The keynote was a sort of inside-out narcissism: artists’ self-absorption as a publicly engulfing phenomenon, under the godlike aegis of Harald Szeemann. Inevitably, one of his subsequent shows—he created about two hundred in his lifetime, mostly as a freelance curator—focussed on the Wagnerian ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the supposedly total art work. In the headily abstract terms by which he functioned, his career can be defined as just that.

Born in Bern, Szeemann studied art history, archeology, and journalism in the city and got a Ph.D. in art history in Paris, at the Sorbonne. In the fifties, he worked in theatre, as an actor and a set designer. Congenitally radical and a connoisseur of mystical, outsider, and folk art, he had organized exhibitions in Switzerland when the Kunsthalle Bern hired him. There, he instituted a hectic policy of monthlong shows. In 1963, he scored a hit internationally with art work by mental patients taken from the collection of the farsighted German art historian and psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn. Five years later, he let the youthfulChristo and Jeanne-Claude wrap the Kunsthalle in translucent polyethylene—their first coup in that line. Incessantly on the move, he scooped up obscure young avant-gardists far and wide, entering into collaboration, and often lifelong correspondence, with them.

Ann Temkin, the chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, is among the many curators who pay him homage. She has described him to me as a “counter-academic” thinker who cast himself as a “wizard/alchemist.” She added that, of course, tactical reversions to the ancient and “primitive” were recurrent modernist tropes. But Szeemann went further. He enhanced the model with jet travel and a visionary, indefinitely utopian afflatus like that of a Buckminster Fuller or a Marshall McLuhan. He embraced Marcel Duchamp’s gaming of boundaries between art and non-art, though with a programmatic zeal that lacked the Frenchman’s witty philosophy of indifference—an often emulated but truly inimitable way of caring about not caring. Szeemann evangelized for disruption.

Szeemann expanded on “Attitudes” with his curatorship of “Documenta 5,” the 1972 edition of the every-five-year granddaddy of international roundup exhibitions, in Kassel, then in West Germany. (A manageable drive, into the Harz mountains, took you to the multi-fenced, guard-towered, dog-patrolled border of East Germany.) Prominent critics damned the show as “vulgar,” “sadistic,” “monstrous,” and “overtly deranged.” Negativity aside, those weren’t baseless judgments. The mélange of post-minimal, conceptual, and outsider art, punctuated with happenings and performances, pointedly insulted good and even bad taste and resulted in addled discourse. It’s time for me to confess that, while in awe of his genius, I resent Szeemann’s legacy: a still swarming spawn of theme-heavy, curator-über-alles biennials, worldwide. The model is effectively critic-proof and, in its later, festivalist phases, all but viewer-proof, too—an enervating circus.

It’s unfair to blame Szeemann for the faults of his epigones. Unlike most of them, he was exquisitely sensitive to formal and poetic qualities in art. No matter how far-out the conception of his shows might be, they looked great. Artists he favored—who notably included the painter Cy Twombly, in the teeth of trendy declarations of the “death of painting”—had to have mastered the means and materials of their craft, at least enough to drive home their ideas. Still, Szeemann stands accountable for the paradigm of the authoritarian mega-show. Speaking of avatars, I fancy that Szeemann was to art exhibition somewhat as Robert Moses was to urban planning: demolishing landmarks in favor of slashing thruways, with an added feature of intellectual off-ramps that loop back onto the main road, zooming nowhere.

“Grandfather” is zoom distilled. There’s no excuse for it except virtuosity. Étienne Szeemann comes off as a mildly colorful character, who cultivated a reputation for chic modernity in hairdressing and served theatre and opera companies with flamboyant re-creations of historical styles. The rare sign of a taste for modern art is a reproduction of a drawing by Jean Cocteau. (Treasure hunt: find it.) None of the assembled items would startle if encountered in an upscale antique store or a particularly appetizing flea market. The artistic experience, irresistibly intense, involves nuances of thematic consideration and formal order. Layouts of combs and brushes, curling irons, razors, dye containers, soaps, hair samples, jewelry, and such feel not repetitive but satisfyingly completist: familial reunions of associated objects, each secreting a tellable tale. Though hardly an inch of space is left bare in the show, there’s no sense of clutter. Rather, there’s an orchestration of contrapuntal harmonies. The aesthetic totality engulfs and exalts the variable charms of its parts.

Szeemann concocted “Grandfather” while in retreat from the furies of controversy that greeted “Documenta 5.” He had already been hounded from the Kunsthalle Bern by citizens who hated “Attitudes” and were disgruntled by his resistance to showing local artists. No single institution could contain his manias, which developed along tracks that included what he termed his Museum of Obsessions—casting his own sensibility as a net for art and artifacts of past and present cults and solipsistic individuals. The effect lost force as the luck of Szeemann’s intersection with the art movements of the late sixties and early seventies faded. Given the atomized pluralism of art today, his many heirs in the role of the globe-trotting curatorial impresario—inescapably, the likewise Swiss Hans Ulrich Obrist—are reduced to theatricalizing ideas that churn rather than advance thinking about art for art’s sake.

Is obsession a psychological recourse from depression? (If so, my life experience disposes me to take my chances with the latter.) I don’t know if Szeemann was depressive, but the forced insouciance of “Grandfather” suggests buried memories of family drama and feelings of loss. Like a carrousel ride, obsession yields a sensation of motion while circling past views that are ever the same. That pattern produced thrills of novelty when Szeemann, like many brilliant artists of his halcyon moment, introduced it to pronounce an epochal abandonment of modernism’s mythology of progress. But it’s an exhausted story now. Even the faith’s rump formulation, postmodernism, wilts. Thinking of what Szeemann wrought, I’m haunted by a Noël Coward line: “Why must the show go on?” The “why” is what matters now. Even unanswered, that ought to keep anyone who is concerned with creating or mediating culture anxiously preoccupied.

by Peter Schjeldahl