James Bantone: 202420242024 | Artnet

Dec 17 2024

How Mannequins Inspired James Bantone’s Meditation on the Fragmented Body

In his new exhibition “Scrap” at New York Life Gallery in Lower Manhattan, Swiss artist James Bantone explores disintegration and identity.

James Bantone works with objects that were once subjects and subjects in states of disintegration. In his newest body of work, a series of acrylic transfers on metal plates, the Geneva-born and Paris-based artist’s interest in today’s forces of objectification and commodification revolves around one form in particular: the mannequin. “As much as I feel like the mannequin is the ultimate metaphor for the body as an object,” Bantone said. “These works are also ultimate metaphors for the body as a commodity.”

His latest exhibition, “Scrap,” fits right into the program at New York Life Gallery, an artist-run space tucked away on the fifth-floor of an unassuming building in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Since 2022, photographer Ethan James Green, who himself shoots regularly for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, has established his keen eye at the gallery for emerging artists with a proximity to fashion. Bantone’s mannequin studies make perfect sense in this context, which has been host to Drake Carr’s live drawing show borrowing from the vernacular of fashion illustrations and the publication of zines by photographer Sam Penn who’s shot for brands like Balenciaga and Vaquera.

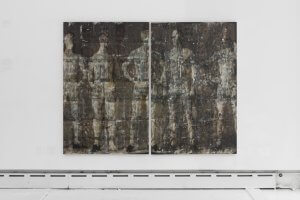

For “Scrap,” on view through January 25, the artist sourced his material from mannequin catalogs. He then transferred scanned images advertising the different available versions of the mannequins on offer onto metal in varying degrees of repetition, manipulation, and transparency. Bantone sprayed each steel sheet with vinegar, producing a layer of rust that he then scratched at.

In some compositions, the mannequin appears as a kneeling headless figure amidst an alchemical void. In others, Bantone brings the human back into the fold. Several works in “Scrap” feature an image of the mannequin side by side with the image of the person it was based off of. These counterparts appear on the same plane, like a before-and-after split screen. “Trying to put those two images next to each other emphasizes how the mannequin becomes such an abstract image,” Bantone said.

In many ways, “Scrap” is the extension of Bantone’s Swiss Institute exhibition “202420242024” which opened this past March and marked the 32-year-old’s solo debut in the U.S. It was on this occasion that he began sourcing images from retail mannequin catalogs that he either spontaneously came across online or ordered on eBay.

The mannequin was a perfect conceptual development, furthering ideas of representational refusal and anti-consumability already integral to Bantone’s practice, which spans photography, video, and sculpture. He had previously realized these aesthetic negations through a variety of techniques, applying abject prosthetics onto models’ faces and deliberately projecting his own shadow onto photographic subjects. Upon discovering the potential of the mannequin, Bantone took a different direction with “202420242024.” “I decided not to work with models at all anymore,” Bantone said. “I started to use the mannequin as the base of my reflection.”

Bantone’s approach to photography shifted too. “There was a lot of ego, where I wanted to run photography that was more, let’s say, unique,” Bantone explained. Luckily, the streets of Lower Manhattan offered a solution. “One thing that really marked me was all the advertisements in the streets,” the artist said. “When you walk toward the Swiss Institute, as well, there are these wood panels and all these series of ads or campaign images for different fashion brands that are glued on them. You have this new layer of images that come every week.” The repetitive nature of this advertising, where the layering of editorial-quality images normalizes specific conceptions of beauty and bodies, resonated with the power that Bantone had identified in the mannequin.

Bantone began trying to reproduce these wheatpaste advertisements by transferring Xeroxed images from the mannequin catalogs, but he was ultimately not pleased with the wood panels. Back in Paris, he noticed a form of advertising on metal fences, which inspired him to instead transfer the images onto discarded metal plates. The result was a series of 16 acrylic transfers on steel sheets. In some of the works, the mannequins are repeated in askew grids. In others, they are distorted to the point of fuzzy illegibility or outright abstraction.

Such use of the mannequin undeniably connects Bantone’s work to artists like Paul McCarthy, Charles Ray, and even Mike Kelley, whose use of mannequins and dolls not only signals consumerism’s material and ideological excesses but also underscores the uncanniness that one encounters more with each day. However, unlike the aforementioned artists, Bantone’s incorporation of both the human and mannequin ultimately emphasizes the urgency of his critique. After all, the conflation communicates the ubiquitous, albeit unevenly exercised, objectification faced by everyone today. Thus, in collapsing the mannequin and the subject they were modeled from on discarded, rusted, and scratched surfaces, Bantone materially tethers the weathered “use of the body” to the “use of the metal sheet itself.”

While the mannequin and human are often clearly demarcated through lines and grids in these works, the degree of opacity and repetition to which the images are subjected produces an element of confusion. In “Scrap,” on a 19-by-24-inch steel plate, the image of a human head seems at first glance to be repeated 16 times. On further inspection, the image in the second row is blotted to the point of abstraction and the third row merely reproduces the top half of the face, making it impossible to definitively classify the subject as human across all the views. This identitarian limit, imposed on both mannequin and model throughout “Scrap,” is crucial to Bantone. “That’s the core of the work,” he said. “Having this discourse on how identity disintegrates itself trying to reach some kind of perfection or trying to fit some mold that makes it more sellable to the larger public.”

For Bantone, these works are representations of Michael Foucault’s concept of the “entrepreneur of the self,” the post-structuralist theorist’s term for the particular type of self-objectifying and self-marketing subject produced under neoliberalism. They are also a response to the self-commodification that specifically afflicts social media users. “You really have to sell yourself to be able to survive,” the artist explained.

It’s also under these conditions that notions of subject and object falter. Rather than focusing on the already-objectified, as he did in “202420242024,” the works in “Scrap” often portray those transitional states “where the subject becomes the object and everything is an object.” Bantone cites Judy Chicago’s banquet table installation The Dinner Party (1974-99) as an inspiration for the latter.

That he renders this transformation even further with his distressing techniques points to the influence that his own hand has in the matter. The manually scratched-at rust underscores a layered sense of self-awareness, suggesting the self-effacing, self-objectifying, and self-marketing forces of modern subjectivity.

At the same time, Bantone’s mark-making is also an aesthetic rebuttal. The depth it etches obscures transparency as soon as it gestures the artist’s bodily presence, ultimately obscuring the image as a whole. In this move from surface to depth, clarity to obscurity, the layered, rhythmic, and erratic qualities of the marks bring to mind the Martinican philosopher Édouard Glissant’s concept of the opaque, which tethers a lack of transparency to the politics of the oppressed. In Poetics of Relation, Glissant argues that transparency is a prerequisite to acceptance in Western thought. The refusal to clarify, that is to reduce, thus takes on a critical dimension in this context—much as it does in “Scrap.”

As Bantone continues his studies of opacity, identity, and simulation, he is considering integrating more of himself into the work. “I’ve always been very coy about using my own image in my work, and that’s something I’m leaning towards more and more, creating this tension and feeling uncomfortable,” he admits. Recently, this has manifested in his own self-objectification. “I’ve been trying to render myself as a mannequin as well,” Bantone explained. Inspired by the kneeling headless mannequins that populate “Scrap,” he has been 3D scanning his body and retouching it to resemble a mannequin. He has found the process to be imperfect, but in a way that is continuous with the identitarian slippages across his mannequin series.

If the gesture of the scrape found across “Scrap” did not already imply a performative current within Bantone’s work, then his recent attempts to turn himself into a mannequin certainly do. When asked if performance might be a necessary step in his self-actualization as a mannequin, he seemed open to the idea. “Already, with the video works, I’ve been working with people that would perform, but I was more the director,” he said with a laugh. “I guess, at some point I’ll have to do it myself.”