Kobby Adi: Cloisters & Instruments | Art Monthly

May 01 2024

By Tom Denman

Kobby Adi

The London-born artist draws on Conceptual Art and West African traditions to undermine western assumptions about form and content ever being separable.

When anxious over-explanation is the norm, it is refreshing when an artist remains true – or is permitted to remain true to the opacity of their work. Kobby Adi’s confident restraint and tricksterish deployment of signs triggers myriad, often unexpected mental images and associations. At his recent solo show at Cabinet in London, the only printed text was a list of works available at the entrance and on a sheet of A4 affixed to the wall (Untitled, 2024) – the print-out is also available as an edition of 50, costing £80, as if to poke fun at the peculiar commerciality of Conceptual Art. The handout contains all the printed text found in the artworks, the more costly edition omits the floorplan, permitting the show’s mainly conceptual works to be freely reimagined in infinite locations – an effect also achievable by folding the free edition in half to reveal only the legend. By disclosing just enough information to animate the exhibition, and by insisting on printed matter as part of the show and not extraneous to it, the artist disperses a playful exchange between exhibition and viewer.

Adi’s five iterations of Instrument, 2023-24, consist of dial thermometers that line the gallery walls, roughly equidistant from each other, each reading slightly under 20°C – ‘the temperature of the space’. Another text, printed boldly on the dial, is said to span the ‘average internal temperature’ of a different mammal, such as an alpaca or a pig. Each dial has an off-perpendicular line, one that suggests where the healthy degree of ‘normality’ lies; I notice that the gallery’s thermostat is actually above the normal limit and reads 23°C. Informed by similar dials (on a car dashboard, for instance), my initial impression is that this line also marks a limit: one where we don’t want to be. Adi’s thermometers are instruments of measure ment-as-representation (or even ‘instruments’ of reproduction), relating our thermoceptive experience of the space to the body temperatures ofanimals, thereby conjuring their presence, to all-too-disquieting effect. Indeed, the invention of temperature measurement, not to mention the politically standardised unit of Celsius, are placed compellingly in Instrument, as if to parody representational norms produced by biological categorisation; values that traumatically recall the colonial practice of race pseudo-science (or ‘race science’).

Further warranting this colonial reference is another component of Adi’s exhibition. On a separate wall are seven variously shaped fragments oflight and pitch dark wood (Untitled, 2023-24), their careful, itemised arrangement is immediately remindful of adisplay in an ethnographic museum. The keyhole-shaped aper tures rimming one of the darker pieces seem to stem from ‘Moorish’ architecture. Another – made out of the same or a similarly dark wood – resembles an axe, with blood-red sticky tape peeling off its ‘handle’. Yet such references are not obviously made by the artist, whose trick, it seems to me, is to bring out the orientalist influence on one’s perceptual schemata, whether one wants it to be there or not. On one of the fragments, a barely legible note isscrawled in French. Checking my crib sheet, I find they come from the workshop of a luthier, or a maker of stringed instruments – a psychogeographic nod to Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, which flourished in the same location as the gallery from 1660 to 1859 (years encompassing the preeminence of Britain’s slave trade, which, it could be argued, funded London’s ‘pleasure’). The suggestion of music also lends an orphic dimension to the assembled work, while a popular dark-toned wood is Granadille d’Aftique (of which some of the fragments here might well be examples), native to the former French colony of Senegal.

At his 2021 show at Goldsmiths CCA, Adi similarly deployed the ‘irrational’ spirituality of wood to subvert dominant, ‘rational’ systems of knowledge. Here, he mounted a pair of folding school benches on the wall, their undersides lumpy with chewing gum (for now, 2020). The iroko wood of the benches continues to be imported from West Africa to the UK without restriction, despite the belief held by the Yoruba that the unpermitted felling of this species of tree can provoke it to reap spiritual vengeance. Adi thus succinctly presents the causal and material entanglement between formal (western) education and formative (colonial) disregard. Maybe his film, which depicts an infected toe, also titled for now, 2020, and included in this exhibition, signifies both wound and curse, as if calling on the iroko for its healing powers.

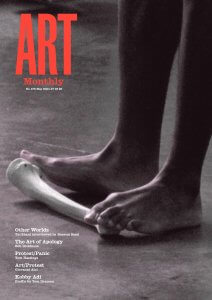

Adi’s films expand on his sculptural work’s interplay of presence and absence, life and death. Lesson, 2023- 24, is a captivating 57-second clip of a bone adhering to a foot – as if bound by some invisible, seemingly magnetic force – that moves on and off the screen, its deathly subject matter transforming the basement gallery of Cabinet into a tomb. Discussing Andres Serrano’s comparable 1992 series of photographs ‘The Morgue’, Mieke Bal noted in her book Quoting Caravaggio that ‘the tomb is the site of death and of the past, as well as of life, in the memory of it that is in the present’. This past cannot be cut off from the reality in which we live now, just as the bone in Adi’s video is affixed to the foot. As connectors to the ground as well as to bodily foundations, our feet are apt metaphors for ancestral attachment. A similar correlation of the life cycle and the earth is played out in Cloisters, 2023-24, exhibited in Adi’s current show at New York’s Swiss Institute, this time zooming in on an apple rotting on the ground. Attending to it is a fly, and then a moth. The apple’s nourishment of the soil extends to the maggots about to hatch, connecting the airborne with the earthbound, and turning the sphere of the fruit into a mini cosmos.

Adi shoots on 16mm, his transfers to video bearing the signs of its materiality, such as flicker and burn effects and jumpy montaging, recalling the structural films of the1960s and 1970s. Except rather than demystifying filmmaking – as structural film sought to do by subordinating content to form – Adi does the opposite, drawing an imperfect equivalence between the medium and his sculptures and positing the cinematic image as an immaterial presence magicked out of materials. He gave playful, modernity-baiting form to this conception of film in his experiments with palm wine, used in West African ritualistic traditions to invoke ancestral spirits. His sculptural assemblage Whiskey, 2022, includes ‘homemade palm wine developer’, while Palm Wine Developer for B/W Motion Picture Film, 2023, consisted of a printed document with instructions on how to make it (both works were exhibited last year in the Whitney Museum’s group show ‘Clocking Out: Time Beyond Management’). That Adi records some of his films – including Cloisters – on medical-grade DVD (designed for ultrasounds, X-rays and the like) enhances his epistemic intervention, with advanced precision oxymoronically magnifying the ‘defects’ of the original negative.

‘Conceptual Artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach.’ This oft-quoted first line of Sol LeWitt’s Sentences on Conceptual Art, 1968, resounds in any encounter with Adi’s work. And yet, Adi takes it to places that LeWitt might not have had in mind, incorporating this mystical leap into a critique of dominant epistemic parameters that are deemed superior on account of their hegemonically determined rationality, logic and secularity.